After sixty years of research, it’s conventional wisdom: as people get older, they stop keeping up with popular music. Whether the demands of parenthood and careers mean devoting less time to pop culture, or just because they’ve succumbed to good old-fashioned taste freeze, music fans beyond a certain age seem to reach a point where their tastes have “matured”.

That’s why the organizers of the Super Bowl — with a median viewer age of 44 — were smart to balance their Katy Perry-headlined halftime show with a showing by Missy Elliott.

Spotify listener data offers a sliced & diced view of each user’s streams. This lets us measure when this effect begins, how quickly the effect develops, and how it’s impacted by demographic factors.

For this study, I started with individual listening data from U.S. Spotify users and combined that with Echo Nest artist popularity data, to generate a metric for the average popularity of the artists a listener streamed in 2014. With that score per user, we can compute a median across all users of a specific age and demographic profile.

What I found was that, on average…

- … while teens’ music taste is dominated by incredibly popular music, this proportion drops steadily through peoples’ 20s, before their tastes “mature” in their early 30s.

- … men and women listen similarly in their their teens, but after that, men’s mainstream music listening decreases much faster than it does for women.

- … at any age, people with children (inferred from listening habits) listen to a smaller amounts of currently-popular music than the average listener of that age.

Personified, “music was better in my day” is a battle being fought between 35-year old fathers and teen girls — with single men and moms in their 20s being pulled in both directions.

COLLECTING THE DATA

Spotify creates a “Taste Profile” for every active user, an internal tool for personalization that includes us how many times a listener has streamed an artist. Separately, we can marry that up to each artist’s popularity rank from The Echo Nest (via artist “hotttnesss”).

To give you an idea of how popularity rank scales, as of January 2015:

- Taylor Swift had a popularity rank of #1

- Eminem had a popularity rank of about #50

- Muse had a popularity rank of about #250

- Alan Jackson had a popularity rank of about #500

- Norah Jones had a popularity rank of about #1000

- Natasha Bedingfield had a current-popularity rank of about #3000

To cut down on cross-cultural differences, I only looked at users in the U.S. Thus, to find 2014 listening history for 27-year-old males on Spotify (based on self-reported registration data), we can find the median popularity rank of the artists that each individual 27-year-old male U.S. listener streamed, and calculate the subsequent median across all such listeners.

DOES AGE REALLY IMPACT THE AMOUNT OF POPULAR MUSIC PEOPLE STREAM?

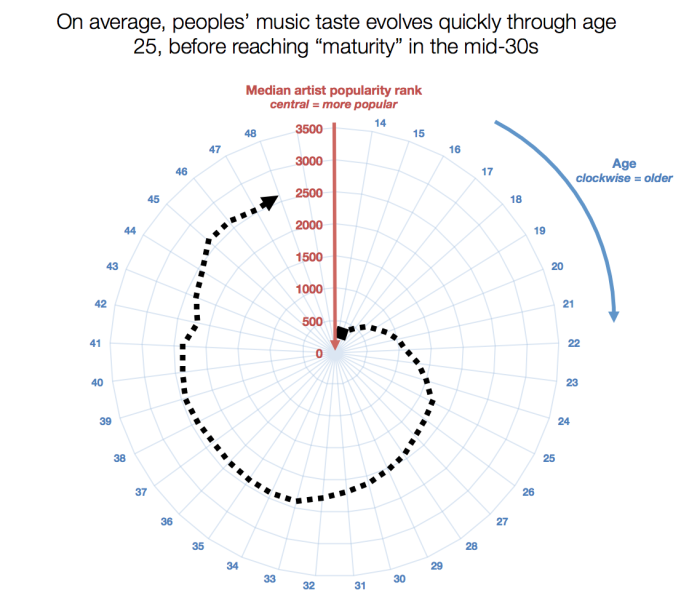

Mainstream artists are at the center of a circle, with each larger concentric ring representing artists of decreasing popularity. The average U.S. teen is very close to the center of the chart — that is, they’re almost exclusively streaming very popular music. Even in the age of media fragmentation, most young listeners start their musical journey among the Billboard 200 before branching out.

And that is exactly what happens next. As users age out of their teens and into their 20s, their path takes them out of the center of the popularity circle. Until their early 30s, mainstream music represents a smaller and smaller proportion of their streaming. And for the average listener, by their mid-30s, their tastes have matured, and they are who they’re going to be.

Two factors drive this transition away from popular music.

First, listeners discover less-familiar music genres that they didn’t hear on FM radio as early teens, from artists with a lower popularity rank. Second, listeners are returning to the music that was popular when they were coming of age — but which has since phased out of popularity.

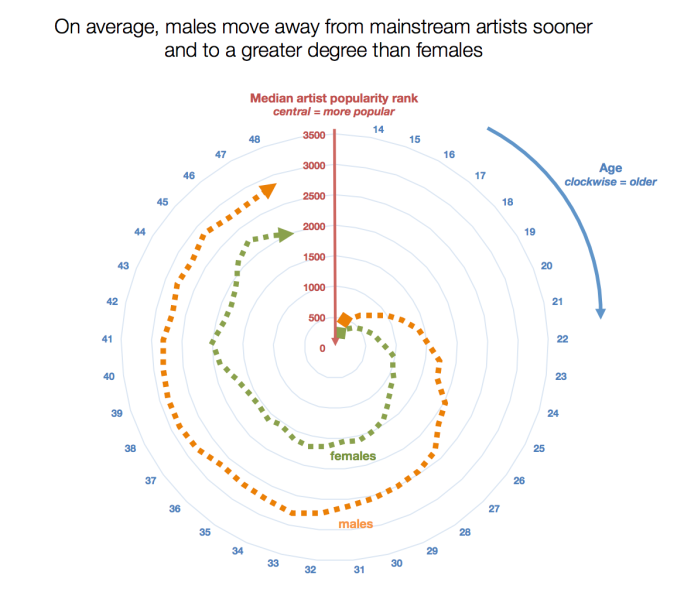

Interestingly, this effect is much more pronounced for men than for women:

For every age bracket, women are more likely to be streaming popular artists than men are. (These days, the top of the charts skew towards female-skewing artists including female solo vocalists, which may contribute to the delta.)

However, the decline in popular music streaming is much steeper for men than for women as well. Women show a slow and steady decline in pop music listening from 13-49, while men drop precipitously starting from their teens until their early 30s, at which point they encounter the “lock-in” effect referenced in the overall user chart earlier.

The concept of taste freeze isn’t unique to men. But is certainly much stronger.

DOES HAVING CHILDREN REALLY IMPACT THE AMOUNT OF POPULAR MUSIC PEOPLE STREAM?

Many factors potentially explain why someone would stop following the latest popular music, and most of them are beyond our ability to measure.

However, one in particular is something we can identify — when a user starts listening to large amounts of children’s music. Or in other words, when someone has become a parent.

Spotify has an extensive library of children’s music, nursery music, etc. By identifying listeners with significant pockets of this music, we can infer which listeners are “likely parents,” then strip out those tracks and analyze the remaining music.

Does having kids accelerate the trend of aging out of music? Or do we see the opposite — i.e. that having kids in the house exposes a person to more popular music than they would otherwise listen to?

In fact, it’s the latter: Even when we account for potential account sharing, users at every age with kids listen to smaller amounts of popular music than the average listener. Put another way, becoming a parent has an equivalent impact on your “music relevancy” as aging about 4 years.

Interestingly, when it comes to parents, we don’t see the same steadily-increasing gap we saw when comparing men and women by age. Instead, this “musical tax” is roughly the same at every age. This makes sense; having a child is a “binary” event. Once it happens, a lot of other things go out the window.

All this is to say that yes, conventional wisdom is “wisdom” for a reason. So if you’re getting older and can’t find yourself staying as relevant as you used to, have no fear — just wait for your kids to become teenagers, and you’ll get exposed to all the popular music of the day once again!

(Though I guess if we’ve learned anything today, it’s that you’ll end up trying to get them to listen to your Built To Spill albums anyway.)

Methodology notes

- For this analysis, I wanted to isolate music taste down to pure music-oriented discovery, not music streamed because of an interest in some other media or some other activity. To that end, I eliminated any Taste Profile activity for artists whose genre indicated another media originally (“cabaret”,”soundtrack”, “movie tunes” “show tunes”, “hollywood”, “broadway”), as well as music clearly tied to another activity ( “sleep”, “environmental”, “relaxative”, “meditation”).

- To identify likely parents, I first identified listeners with notable 2014 listening for genres including “children’s music”, “nursery” , “children’s christmas”, “musica para ninos”, “musique pour enfants”, “viral pop” or ” antiviral pop”, then subsequently removed that music when calculating the user’s median artist popularity rank.

- To control for characteristics across cultures, this analysis looked only at U.S. listeners.

- As has been pointed out in previous analyses, registration data by birth year has a particular problem in overrepresentation at years that end with 0 (1990, 1980, etc). For those years, I took the average value of people who self report as one year younger and one year older. Matching birth year to age can also be problematic depending on month of birth, so for the graph’s sake I’ve displayed three-period moving averages per year.

Interesting data, but from a very limited set. Personally I do not use Spotify and do not know anyone who does. There would be no (easy) way to capture data from those who listen to physical media or purchased downloads.

Very good point –important to remember that this is only a limited slice of someone’s listening, that won’t include, say, iTunes data. (The tradeoff is the ability to capture intent; I may not be bothered to purchase a 90s song that was my jam in high school, but if I’m already on a streaming service it’s easy for me to seek it out and stream it, add it to a playlist, etc so we see that signal in a way we might not otherwise.) It would definitely be interesting to correlate this to, say, FM radio listening… do older people listen to more throwback stations and less Top 40?

Yes I would agree with your point entirely!

Spotify in itself is a very modern music platform. I would think that those older users were showing signs of keeping up with popular platforms by using this service! My mum as an example would have no idea what spotify was!

I found this analysis really interesting! But some of it is hard to interpret. For example, one could look at that parents graph and take it to mean that parents have more adventurous/exploratory taste than non-parents. Doesn’t seem likely to me, but it’s all in how you analyze the data.

As someone who almost exclusively listens to official soundtracks from movies, television, and video games, I was somewhat saddened to see that OST’s were not considered. I feel as if this implicitly supports the notion that soundtracks do not have intrinsic value when removed from their intended context.

I know a bar chart isn’t as sexy, but your charts are incomprehensible.

You said something interesting:

First, listeners discover less-familiar music genres that they didn’t hear on FM radio as early teens, from artists with a lower popularity rank. Second, listeners are returning to the music that was popular when they were coming of age — but which has since phased out of popularity.

Is there any way to separate those two factors?

why the polar plots? a straight line-graph would be much easier to read.

i would say it’s about nostalgia http://bit.ly/1zW0lU7

Im not totally clear on how music relevancy is measured in echonest, but couldn’t it be more accurate to compare the release dates of each song listened to? In my experience the maturing of music tastes also means a broadening of genres beyond pop, not necessarily the endless repetition of a few albums from your teens.. It might be brand new music, but it’s “relevancy” is low because it doesn’t appeal to the largest listening market. Is there anything in the data that could confirm this thesis?

It is an interesting slice of date but for me personally this has absolutely no relevance. I do not stream music (for reasons of principle), I am well into middle age, and I have to say that I have found more new music (and new genres), in the past decade than I have in all the rest of my music-listening life put together. Right now I listen to a vaster range of music than I did in my 30s.

I shared this to my fb page and my music-loving friends there are basically reacting the same way. Are we all outliers or is this conclusion so limited it has to be qualified all to hell?

Reblogged this on Colorado Music & Radio and commented:

in radio 37 yrs. We “knew” this info in the 80s, when the “cutoff” was 24, not 34. good info

Can you share the data?

Thought provoking – thanks for doing this. There is a phenomenon that is rarely observed in this kind of survey. That is there was a period in the late 60s into the 70s when there was “popular” music and “underground”. !in 1973, for example, the singles charts were dominated by Vicki Lawrence, Tony Orlando, Helen Reddy, Jim Croce, and Grand Funk Railroad, most of whom are forgotten today. However, Pink Floyd released Dark Side of The Moon which didn’t have a hit single until years later. These days we think of Pink Floyd as being the “popular” music of its day, but it really wasn’t.

this is a very narrow slice. I also don’t use spotify or echonest. I mostly hear new music (and I’m discovering new music each week) on Youtube, and FM or streamed FM radio (WXRT Chicago and WYEP Pittsburgh) I am 62 years old and never have stopped listening to or discovering new music. The definition of “new” needs to be separated from “popular” or top-40 hit list. Often time I’ll discover a new artist, who has been around a few years but is new to me. Same is true for young people just starting to pay attention to music, discovering “new” classical that is new to them.

Okay, actual social scientist here. This is a terrible analysis, and I’m here to tell you why.

For one thing, popularity rank clearly has nothing to do with any quality of the music. In the article’s very own example:

“Taylor Swift had a popularity rank of #1 [while] Natasha Bedingfield had a current-popularity rank of about #3000.”

Yet a quick listen of Natasha Bedingfield’s music will show that it is completely standard pop music which doesn’t stray far from the Taylor Swift formula (although Swift is a much more masterful composer of those elements). What should we surmise about someone who enjoys Bedingfield instead of Swift? I think, instead, that popularity rank doesn’t actually tell us a single useful thing about the people listening to music.

Furthermore, since this only samples Spotify users, and popularity rank only tells us about the average number of spotify listeners a musician has, we can’t actually learn anything about how age impacts our listening habits, except that on average, US spotify listeners start out listening to lots of billboard hits and then expand their taste.

US Spotify users who are age 33 or older tend to have a similar amount of average popularity ranking, but all this tell us is that the music they listen to, on Spotify, is of overall the same average popularity. Maybe this means that Spotify has a limited selection and doesn’t accurately track people’s rare (“unpopular”) listens. Maybe it means that people explore rare and popular music in equal amounts. It could mean any number of things! It’s extremely limited data.

Finally, and most egregiously, what really pisses me off about this article is that it takes two of the exact same trends but labels it two different things in two different populations. When the population is about men, the article says that “the decline in popular music streaming is much steeper for men than for women,” implying that men are weaned off pop music and discover much more interesting and rarified music. However, the same trend, when applied to parents, is “a decline in musical relevancy,” whatever that’s supposed to mean. Why the different treatment and analysis for the exact same data trend?

This is not a very good article at all. If anything, it is instead a pristine example of how the prejudices of the researcher have influenced the very analysis of their own data.

p.s. why the hell did you graph age, a linear attribute, as a circle?

Isn’t this all a bit circular? And I’m not just talking about the graphs 🙂

Teenagers are the best fit for the profile of people who listen to popular music. But isn’t that because teens define what popular music is? They have the most time, social opportunity and social pressure to listen to pop music, and they have the least diversity of experience and taste to be diverted off into. The article says that one reason older people don’t listen to such popular music is because they listen to music that was popular when they were teenagers, and that music is less popular now – as if it’s inevitable, a definition, that music that isn’t listened to by current teens isn’t as popular. So that’s defining popular music as music listened to by current teens, defining less-popular music as music not listened to by current teens, and then measuring who listens to this category of less-popular music that current teens don’t listen to, by measuring who listens to less-popular music that current teens don’t listen to… which they don’t listen to because, by definition, they’re not current teens. You can’t use the measure as the data!

My other problem is with the idea that this gives any evidence of taste freeze or a ‘music was better in my day’ position. (I’m not arguing that this doesn’t exist, or isn’t probably true for a majority of people, only that the data we have here doesn’t tell us anything about it.) The article discusses two types of less-popular artist: someone who used to be mainstream-popular when that listener was a teen and isn’t any more, and more diverse, never-popular artists that listeners discovered in their twenties. So what about artists who were big in their time, but that time wasn’t when that listener was a teen? Or new, not-popular-yet artists playing new styles? Or old artists who have developed and are playing new styles? You could argue (I think it’s argued above) that new, never-going-to-be-popular artists make more innovative music than current mainstream pop artists, so how is someone suffering from taste freeze by listening to them? We can tell that forty-year-olds are listening to less-popular music, but we can’t tell whether that’s because they’re listening to pop from 25 years ago, a more obscure band they picked up in their twenties and are still listening to, or a new band playing a style of music that didn’t exist in their teens or twenties. (I’m 39, and I like the break-beat jazz/acoustic electronica band GoGo Penguin – they didn’t exist when I was a teenager, and since I was mostly listening to rock and metal then, I wouldn’t have liked them if they did. Do I think music was better in my day because I listen to GoGo Penguin and not Taylor Swift?) It’s the same circular problem – you can’t bring in the concept of taste freeze to explain why people *might* be listening to less-popular artists, and then use the fact they they’re listening to less-popular artists as evidence of taste freeze.

TL,DR: All this data shows is that when you measure whether people listen to the music teenagers listen to or whether they listen to the music that people who are no longer teenagers listen to, defined by whether they listen to the music teenagers listen to or the music that teenagers don’t listen to, you find that people who aren’t teenagers listen to music that people who aren’t teenagers listen to. No wonder the results seem so clear…

Good effort at getting the data to prove any smart person’s instincts right. As I would like to say, all Instincts are experiments only Data is proof.

Interesting. However there are vitally missing pieces:

1. The way music is consumed (MP3 vs. the heyday of the CD in the 90s). It’s interesting that when the curve starts to dip back in, that range, from 33 to 41 really is the first MP3 generation.

2. How accessible the internet has made music, relinquishing most artists of their mystique. (Back in the day you’d get brief glimpses in fanzines, mail order catalogs, stories heard by older brothers’ friends, and maybe you’d get into an all ages club on a school night, and make out with a truly limited to 200 7″, etc.)

3. How easy it is to record music now.

As a lifelong music nutcase, male, 38, unmarried, no children, and someone that’s consciously tried to keep his pulse on good (don’t read that as hip) music, I really don’t think music is as good now as it used to be. The playing field leveling caused by the things mentioned above has provided too many entrants, I should say too many subpar entrants. The turf war between major labels and independents produced some remarkable music in the 80s and 90s; each in their own way silencing a lot of the bands that should have been silenced, boiling up some amazing voices in their collective wakes. I could go on for a mile about bands like the Minutemen, to albums like Endtroducing…, and Loveless.

Despite the ubiquity of year end lists, I’m not even sure I can come up with a list of new(ish) bands that are truly exciting right now. Even really amazing bands, like Viet Cong, are throwbacks, not that that’s a bad things because what they do they do extremely well, but it’s not new. It feels like all the truly new ideas died with the CD. There are sub, sub, sub genres, but there aren’t movements. And to the younger kids that will disagree, all I can say is that if there were parallel lives, and you could have lived through the music I lived through, music that simultaneously gave a nod to the masters (of course we consumed all the greats while we consumed our generation’s music), while marking a new direction; I think you’d agree with me.

But what do I know, I’m from the same generation that gave the world Creed and Linkin Park?